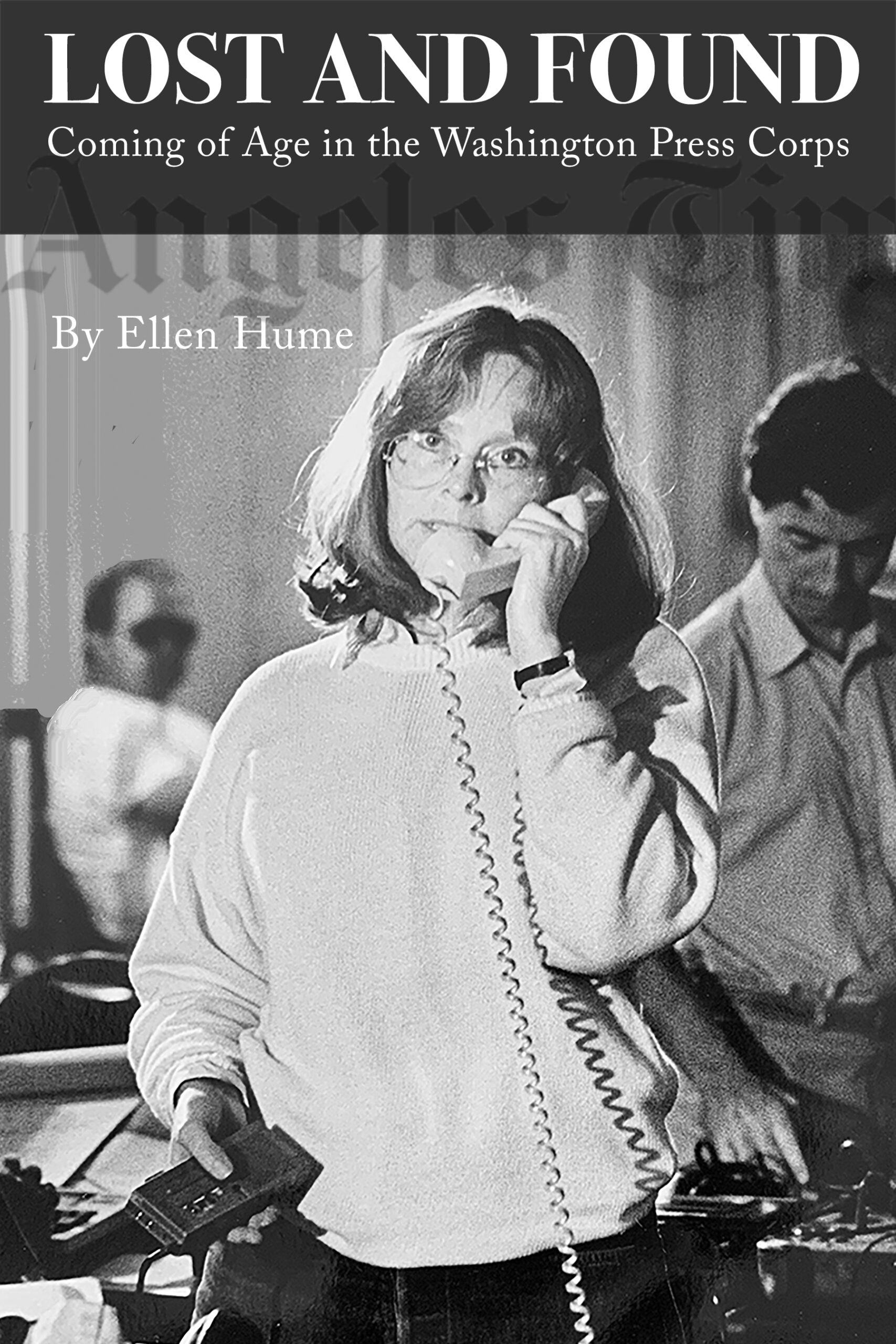

Fun and Games in the Washington Press Corps

You can order it from your independent bookstore, from Amazon.com, or from Bookbaby…

You can order it from your independent bookstore, from Amazon.com, or from Bookbaby…

Here are the insider tricks to figure out if a news item is true or not. Please share this PSA which contains some basic media literacy guidelines so that you don’t get duped by those who want to use you to spread their lies.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i3rDP_boUYw&feature=youtu.be

I’m happy to see this new initiative that helps us identify the real journalists who offer trusted work, with accountability. Now we need to get more media literacy, so consumers will know to use tools like this Transparency Tracker to select reality-based, fact-based journalism providers instead of falling prey to the propagandists, newsbots and conspiracy theorists who are making money or gaining power by duping us into spreading and believing stuff that isn’t true.

Most importantly, tools like this confirm that some content is much more trustworthy than other content You CAN figure out what is useful news from what is propaganda. Don’t be left powerless by cynicism that tells you everything is a scam. If you decide that, you will never be able to hold the bad guys to account.

Journalism has never been, and will never be, perfect. But it is a tragedy when people don’t understand who is working in the public interest, to help empower them with information, versus all those jerks who are trying to sell them something for their own amusement or ill-gotten gains.

This was the question we were chewing over at Gerbaud’s legendary Budapest patisserie yesterday. I was with two of the most experienced and creative thinkers about global media: Rosental Alves of the University of Texas, who knows everyone and everything about Latin America journalism, and Behrouz Afagh, head of the BBC’s Asia and Pacific news coverage. The day before, we had all heard a terrific idea from Fred Ritchin, the USA dean of news photographers, now a New York University photography professor because he left as photo head of the New York Times in 1982.

Here is Fred’s idea: when you digitally publish a serious news photo you imbed a link on the left corner of the image, that when moused over, shows a “before” image taken of the same subject just before the selected image, and in the right top corner, a link that shows an “after” shot taken just after the main image. It’s a way of seeing whether the selected image was constructed or was actually taken–as authentic photojournalism is supposed to be– from a real flow of action. This process itself could be faked, of course, as can almost everything now. But there would be a low incentive to fake these contextualizing “before” and “after” shots, since the point is that they would be voluntarily included by those who are trying to hold themselves accountable to a professional standard of veracity.

This kind of device, which unfortunately didn’t capture the imagination of our colleague Ethan Zuckerman at the MIT Media lab when we posed it to him as something we would like to see his designers create, is related to my own long-fantasized authentication tool. I would like a tool that would enable those who want to be held to a veracity standard (a “Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval.”)

Of course, those doing risky communication would forgo using this history bug, in order not to be tracked down. This is sort of the opposite of Tor. (All tools can be used for evil. That doesn’t mean we should shy away from creating new tools.)

For those who are working hard to offer or find verified, authenticated facts and images, this little bug could offer a missing accountability factor. If people understand where a story (or image) comes from, they might know more about what credibility to give it. It could be introduced on a voluntary basis by the purveyors whose vetting is considered essential to their brand (New York Times, BBC.) This wouldn’t solve all the problems of critically evaluating the flow of content, but it would give us a tool we could sorely use.

If you add another feature—an automated or nonautomated micropayment feature that is tied to the authentification—then you might just have an interesting tool that would not only help people figure out what to take seriously, but would pay for this higher veracity stuff, supporting the often expensive production of investigative journalism and other hard-to-get vetted and contextualized news items.

Anyone like/hate these ideas? Your feedback is awaited.

Or on any day of the week, look at how Glenn Beck or Bill O’Reilly or Ann Coulter or Laura Ingram push their mythical versions of Obama and US history out to the public. Are they lying? Yes! Do they know they are lying? I’m not sure. Reality and fantasy have merged into a coherent political vision that has real traction out there. Just look at the Tea Party guy who didn’t realize the “government” that he hates provides the Medicare that he loves.

So maybe its time to organize some more effective journalistic fact-checking. We need to take the great fact-checking websites: http://www.snopes.com/ for urban legends, and http://www.politifact.com/ and http://www.factcheck.org/ for USA political assertions, and connect them with red and green hyperlinks from the news texts to their findings.

So if a story about Obama or Romney making assertions is filled with green words, that means the links will show those statements to be factually pretty good. But if they are filled with red words, that means the links will show how the statement is distorted or untrue. By clicking on each green or red word, you could read each reference (like a footnote) that would tell you why it’s demonstrably true or false.

If the journalism is presented in paper, rather than digital form, you could place the story in the middle of white space, and then have cartoon balloons going off on all sides framing the story, each telling whether the phrase is true, and on what basis we determined that.

I have long fantasized about having a tag on information that floats around the internet—kind of a “Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval” that would indicate transparently the story’s original source and verification. The food chain of a factoid would then be visible—we could see whether it started out as malware, or whether it really appeared in that official budget document.

The sad part is I don’t think proving something is false will automatically take away its power to appeal. I’m remembering the “Swift Boat veterans” lying about John Kerry’s role during the Vietnam War, in a tremendously effective attack that he failed to counter. A woman interviewed by the NYTimes was asked if she knew the allegations were false, and what she thought when she was shown conclusively that they were. “It doesn’t make any difference,” she said; she still hated John Kerry.

Fairy tales would be fine if they weren’t the basis for going to war, and electing those who might choose do that again on the basis of other fairy tales. So we have to keep looking for ways to persuade people not only to figure out what is true and false…but to care and act on those facts.