Jan. 10-13 Twentynine Palms, CA

We also saw more than one America, as we were driving across the continent to get here. There were rich Americans living in porticoed estates, next to poor Americans, in unpainted wooden shacks. There were Black American slave descendants, still waiting table for the white heirs to antebellum privilege, in unsustainable plantation houses that rented out rooms for the night. The original Native Americans were both everywhere and nowhere, thanks to relentless efforts by European, Hispanic and other interlopers to take over their territory. We met white Christians and black Christians, intimately close on the radio airwaves, but far apart in the physical world. There were East Asian immigrants working at gas stations, and fourth-generation Appalachian truckers who paid them for a cup of coffee. Underneath it all was the hot magma of politics, ready to spew forth at the slightest provocation: volcanic Trump fans and anti-Trump fanatics, who couldn’t stand to think about each other’s worthy existence. They were all Americans, engaging somehow in the same national destiny, without the common bonds of blood, history, or plans for tomorrow.

John booked us a romantic retreat at Campbell House in Twentynine Palms, which, appropriately, was deserted. We loved the story of the stone house’s construction in the mid- 1920s, by disreputable newlyweds. Elizabeth Crozer, a Philadelphia debutante, was disinherited when she ran off to marry Bill Campbell, an orphan who’d been injured by mustard gas in WW1. They were advised by Dr. James Luckie of Pasadena that the desert might heal his damaged lungs. The advice was brilliant. Bill survived another 20 years, long enough to live through the next world war, from their desert redoubt.

-

Campbell House Dining Room

-

Betty and Bill

-

This was part of their original shack, now the office

-

Zip a De Doo Dah

-

Elizabeth Campbell's 1961 Memoir

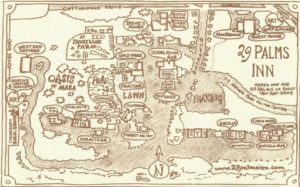

The healing qualities of the desert air were especially good news for us, since John and I were still coughing like crazy from the colds we picked up in the South. We got a little lost on our first night, driving under faint stars in the desert’s famously dark sky, to the Twentynine Palms Inn for dinner. It was great to finally be in Southern California, at the edge of the legendary Joshua Tree National Park! We felt better already. Was it the desert air, the live bluegrass music, or the margaritas? We waited for two seats at the bar, crowding in among the locals. This place had a special vibe, a kind of desert version of Rick’s legendary Casablanca café.

When the young Campbells camped out in the winter of 1924-5, in an isolated tent near the Mara Oasis, having a named Twentynine Palms was still a mirage, There were just seven or eight other shacks. The Campbells mingled with the Native American nomads who watered seasonally at the oasis, and became avid archeologists, documenting the earliest human life in the area. http://campbellhouse29palms.com/history.php

Elizabeth’s father relented and she received her inheritance, so they built their 1929 estate on 25 acres of high desert. After Elizabeth died in 1971, the children sold the property to the composer who wrote “Zip-a-de-Doo-Dah.” He turned it into a Hollywood party house. An English aristocrat then bought the place, installing her china teapot collection and renaming it Roughly Manor. Today it is the quirky Campbell House B&B, honoring the young couple who started their runaway marriage here.

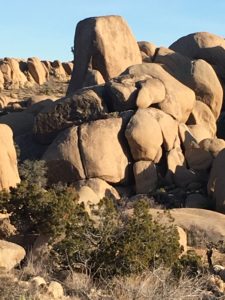

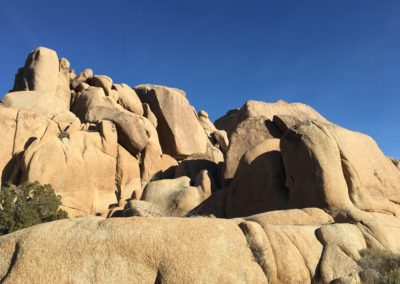

We stopped at the Joshua Tree National Park headquarters the next day, full of rookie questions. What are Joshua trees, anyway? They looked like frenzied cactuses, arms all akimbo. They are actually short-spiked agave plants, the ranger explained. The smaller chocotillo cactuses, other denizens of this desert, grew huddled together like a tribe of chattering monkeys. And then there were the enormous sand-colored rocks, balancing against each other in random formations. What mighty force could have pushed them into such improbable dependancies?

We drove half and hour to lunch in the nearby hippie town of Joshua Tree, but took a wrong turn. We found ourselves dead-ending into a very large, official sign that said “Live Combat Zone. 100% I.D. required.” U.S. Marines came out of a formidable guard post to confront us. We turned the car around very, very quickly. It was a relief to find the right road, and stumble into the Crossroads Café. Its dreadlocked and tattooed waiters were escapees from places like East Harlem and Boston, and they occupied a completely different world from the Marine base close by.

The Crossroads Cafe

We learned that like everywhere else, the Native Americans had a terrible time in this area, as the newer Americans took over in the 20th century. There was the tragic death of a gifted Indian runner named Willie Boy, who fell in love with a non-Indian girl and committed suicide in 1909, after being framed for her murder. Folks are sorry about it now. What was done, is done, but that doesn’t mean it’s over with.

On our second night, as we took up our favorite perch at the Twentynine Palms Inn bar, we struck up a conversation with the folks sitting next to us. Some were from the local community college, and some from the Marine base. They were all friends. After hearing them talk about military things, I asked “What do you think about North Korea?” Their reaction was swift and unanimous: if Trump hit the nuclear button, General Mattis, the Secretary of Defense, would save us. He was sane, even if the Presidents of the United States and North Korea were not. One speaker said he grew up on various military bases, with a father who served in Vietnam. “I’m grateful for being exposed to the wider world,” he said, “so I know what Trump is.” How can we talk to Trump voters now? I asked innocently, holding my breath. “You don’t,” he said firmly. “You talk to them with your votes.”

Skull Rock

The next day was our last at Joshua Tree, so we took an especially long hike, on a path through the giant desert rocks. We watched for rattlesnakes that never appeared, stopping at Skull Rock, the Keys View lookout, and Barker Dam. I imagined the Campbells, carefully labeling Indian artifacts there, and the cattle rustlers and gold prospectors who died seeking their fortunes. To John, some rocks looked like sleeping elephant seals, and I saw others that were petrified whales or ghosts.

In the afternoon we stopped by the former one-room Twentynine Palms schoolhouse, now a museum. Normal glassware, left in the sun, would turn purple in the old days. The tiny museum was crowded with gray-haired visitors, one carrying an oxygen tank, another leaning on her walker. They were listening intently to an aged volunteer, who was glorifying the pioneers.They were oohing and ahing at a gold mine shaft.

The past: mining gold

Old people are building the past, I realized, looking around me. Young people are building the future.

We were going to be back on the road the next morning, driving north through Barstow, toward our San Francisco goal. In two days, we would be living in yet another America, the unstable epicenter of its high tech industries, where twentysomethings are mining artificial intelligence and virtual realities to invent another brave new world.

On our last night in Twentynine Palms, we watched a wobbly old videotape of John Huston’s “Grapes of Wrath,” which even in its original black and white, is a magnificent movie. It prepared us for the final push of our journey, through Monterey to Salinas, where John Steinbeck worked the lettuce fields and learned everything he needed to know, in order to write one of America’s greatest, and most devastating sagas.