Jan. 13-14: Pioneertown and Hearst’s Enchanted Castle

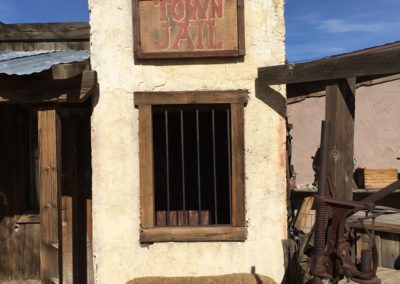

As we left the desert, we couldn’t resist a side trip to Pioneertown, a Wild West film set still popular with tourists. All sorts of Hollywood B movies were made here. Pappy and Harriet’s, the funky café at the edge of town, has hosted famous country and rock performers on stage for 35 years.

After patting a few goats, taking snapshots and fortifying ourselves with iced tea at Pappy and Harriet’s, our desert idyll was over. We headed north, skirting the LA basin past Barstow and Bakersfield, toward Paso Robles.

Unstable Ground

We could have veered west into the dense labyrinth of LA, enjoying some of its Hollywood splendor before heading up the coastal Highway 1. I lived here twice, when I was in my early 20s– first on a Carpinteria mesa where I was a housemother at a boys’ prep school, and then in Malibu, when I had my favorite job as a general assignment reporter for the Los Angeles Times. John and I had planned to stay in Santa Barbara on Jan. 12 to visit my old friend Roxie, who lives on her grandparents’ avocado ranch. But she had to flee in the middle of the night on Jan. 9, as flash floods and mudslides roared by her house. The river of mud killed 21 people in Santa Barbara County, injuring 120 more, and destroying 100 homes.

As we detoured north on Jan. 13, a victim was still missing in the mud, which was blocking all north-south traffic on Santa Barbara’s main highway 101.

http://https://www.cnn.com/2018/01/14/us/southern-california-mudslides/index.html

California is notoriously unstable, which is both its downfall and its genius. The abrupt tectonic movement of the earth, the wild fires and floods, also permeate its culture. In California, the expectation of the new allows people to migrate here and start again, defining themselves as they wish, without the historic constraints of ancestry or neighbors who know who you really are. Change is normal. It’s a place where you have to be young, no matter how old you are.

We drove inland, up the spine of the state, past solar and wind farms, and irrigated fields of citrus and grapes. This was, and always will be, Steinbeck country. A few figures huddled in the fields, picking winter crops. Darkness had already fallen when we finally turned toward the coast at Cambria. We could hear and smell the ocean, but we would have to wait until sunrise, to actually see it.

The next morning we headed down to the musky-smelling sea, walking on wet sand littered with driftwood and long ropes of kelp. We were surprised to see so many old surfers, still mounting the waves in their winter wetsuits.

Hearst’s Hilltop Folly

At Hearst Castle, we boarded a bus for the 5-mile, cliff-clinging ride up Hearst’s mountain. From here, William Randoph Hearst ran one of America’s greatest 20th century media empires, which he used without apology, to his own personal advantage. He took his father’s mining fortune, bought newspapers, and from 1919 to 1947, built this extraordinary set of buildings and gardens in the middle of nowhere. It ultimately encompassed 250,000 acres of prime coastal and grazing land. Aside from a term in Congress, Hearst never had the political career he lusted after. His extraordinary lifestyle on this mountaintop, complete with wild animals and frolicking Hollywood stars, was unsustainable. Now, as a California state park, his castle remains an unparalleled masterpiece, attracting 750,000 paying visitors each year.

Even in today’s era of obscene billionaire mega-mansions, Hearst’s project is the most ambitious private residence ever built in America. Donald Trump couldn’t begin to compete with its excess. The White House is a shack in comparison; Elvis’s Graceland is a broom closet. According to Wikipedia, Hearst’s great mountain top estate “featured 56 bedrooms, 61 bathrooms, 19 sitting rooms, 127 acres of gardens, indoor and outdoor swimming pools, tennis courts, a movie theater, an airfield, and the world’s largest private zoo.” Although he had to sell off his exotic animals after the 1929 stock market crash, a few zebras still mingle today with the cattle herd grazing on the grounds.

Today Hearst Castle is like an aging but still glamorous movie star, dependent on expensive reconstructions, illusions, and memories. For all its hubris, this place is magical. The credit goes to architect Julia Morgan, but apparently Hearst also had a hand in its design. He kept buying bigger tapestries and art works, forcing the exasperated Morgan to redo her carefully proportioned stone walls and ceilings. The estate combines genuine 3,000 year old treasures, including Egyptian, Roman, Greek and Renaissance artworks, mixed with homey touches, like the bottles of ketchup Hearst insisted on serving at his baronial table. Hollywood royalty were his ultimate decorative flourish; they flew in for house parties throughout the 1930s and 40s.

-

-

Priceless tapestries from Europe

-

This is not Elvis's Pool Room

-

And ketchup bottles on the table

-

-

-

-

Ancient Egyptian treasures

-

-

-

-

A 3,000 year old nymph

-

The Roman Neptune pool is being refurbished

-