Donald Trump’s triumphant return to the Pennsylvania site of his first assassination attempt amplifies the threat of violence that is hanging over this US presidential election. Prosecutor Jack Smith has renewed his efforts to hold Trump criminally accountable for the deadly Jan. 6, 2021 insurrection at the Capitol, and two recent near-misses on the former president, along with his own rhetoric, have stoked real concern about more violence ahead.

These events have thrown a new spotlight on another would-be presidential assassin– Sara Jane Moore, the suburban housewife who nearly shot President Gerald Ford in San Francisco 49 years ago. My unwitting direct involvement in Sara Jane Moore’s assassination attempt on Sept. 22, 1975 still haunts me today.

When she aimed her .38 at President Ford from 40 feet away, Sara Jane Moore was someone I mistakenly thought that I knew fairly well. She had tried to call me earlier that morning, and I spoke with her in jail the night afterwards. What she confessed then was traumatic for me, and too awkward for either my newspaper or Sara Jane Moore to admit afterwards.

The full story, which I recount in detail in my memoir, illustrates the remarkable power back then of the mainstream news media, including the Los Angeles Times, before competition from digital media and cell phones changed everything. It also conjures up an extraordinary time in California, which was buzzing with cults and political extremists. The1969 Manson family murders were followed by the 1974 kidnapping of heiress Patty Hearst by a self-styled army of domestic revolutionaries. Manson acolyte Squeaky Fromme’s attempt to shoot President Ford in 1975 was followed just a few weeks later by Moore’s own unrelated attempt. At the same time, Jim Jones was building his apocalyptic cult in San Francisco, eventually persuading over 900 followers to commit suicide together in 1978 by drinking poisoned Kool-Aid at their new home in Guyana.

Today, at age 94, Moore is still a compelling story-teller, a remarkable shape-shifter who inspires people to help her. She is free after more than 30 years in prison, courting a new generation of journalists from her hospital bed in a Nashville nursing home. There is even a new documentary, about her attempt to murder President Ford, which is running this week at the New York Film Festival. I haven’t seen the film, Maybe she will finally tell the whole truth about her precipitating motive, which she shared with me that night in jail.

I had first met “Sally,” as she called herself back then, shortly after I began my dream job in early 1975 as a metro reporter at the Los Angeles Times. Moore became an eager, if unlikely-looking, source for the stories I was doing about the aftermath of the Patty Hearst kidnapping. She appeared to be a frumpy, middle-aged housewife from the suburbs, who had volunteered to help with the Hearst family’s massive food giveaway in San Francisco, to meet the kidnappers’ ransom demand for their 19-year-old daughter. She told me colorful lies about being a Southern belle, omitting the true details of her modest background, her three marriages and the children she had abandoned.

When I began spending time with Moore in the summer of 1975, she had finished with the Hearst food giveaway, but was still hanging out with young leftist radicals in the Bay Area, who were in rival, but overlapping, cadres to the violent Symbionese Liberation Army who had kidnapped Patty Hearst. These clandestine groups included a prison gang called the Tribal Thumb, the Marxist Revolutionary Union, and the Trotskyite October League, Moore was drawn to their intense and purposeful life.

But Moore also responded favorably to the FBI, who hadn’t been able to find Patty Hearst for a year, when they asked her to report on the radicals’ activities. Moore was flattered to be taken so seriously, and became one of their secret informants about her new friends.

Sally simply loved talking with anyone who would listen, and that included me. As a reporter for the Los Angeles Times--then California’s most influential newspaper—I also must have made her feel important. As we met repeatedly in San Francisco that summer, for my research on my series about how Hearst’s SLA kidnappers related to the antiwar and civil rights movements of the 1960s, I realized that Sara Jane “Sally” Moore was herself a colorful story, as an unusual convert to the radical cause. When another FBI snitch she knew named Popeye Jackson was murdered a few blocks from her home in June, she was so terrified that I flew up to San Francisco, where she told me about her own double life. She wanted me to share her FBI history in my article about her, expecting that this would embarrass the FBI, as she publicly broke with them to join the revolution.

I updated my draft accordingly, even though the FBI refused to confirm her relationship with them. I told Sally that her profile would have to wait for a while, because it would be running as a color sidebar within the series, which wasn’t finished yet.

My colleague Narda and were wrapping up the series when Patty Hearst was arrested with her SLA associates in San Francisco on Sept. 18, and the Los Angeles Times needed to start publishing it immediately. We worked around the clock, and our first story ran on page one, Monday, Sept. 22, in the middle of all the splashy Patty Hearst/SLA arrest followups.

I hadn’t seen the paper yet that day, when Sara Jane Moore phoned me at 9 a.m. through the Los Angeles Times switchboard. She’d become a pest in recent weeks, calling me constantly to gossip about her radical friends, and now I needed some sleep. I asked the operator to tell her to phone back later. When I got to the office at noon, all the editors were gathered around my desk, waiting for me, waving new wire stories from San Francisco. Sally had just been arrested for pulling a handgun out of her purse and trying to shoot President Ford! She missed only because a quick-thinking bystander grabbed her arm as the gun went off.

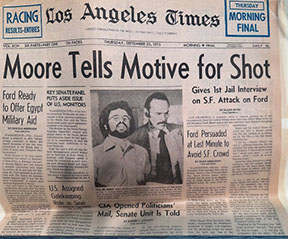

Horrified that I had refused to take her call just a few hours before—which I believed could have stopped this insane act– I rewrote my Sally sidebar into a page one profile of the would-be assassin, including the false details she had told me about her “blueblood” background. I was still in shock when, a few hours later, Sally’s lawyer called me urgently to come up to San Francisco! Sally wouldn’t cooperate in her own defense, he said, until she talked to me.

My exclusive jailhouse interview the next night with Sara Jane “Sally” Moore, the unlikely assassin, ran in virtually every newspaper in the world. I faithfully reported what she told me that night in jail, including her insistence that she wanted to serve the radical cause and break with the FBI.

But my editors cut out an essential and embarassing detail, which implicated me and our newspaper directly in the whole affair: When I asked Sally directly why she tried to kill the president, she blurted out that she did it because my profile of her had been “killed” by the FBI, since it hadn’t appeared in the Los Angeles Times that morning, with first story in our radicals series. Stunned, I had to tell her that the FBI couldn’t do that, and nobody had killed the story. The reason her profile didn’t appear that Monday was that it wasn’t supposed to run until Wednesday, along with part three of the series.

“Oh,” she said, looking downcast. She seemed confused and unsure what to say next, including when I asked her how she would have served the “revolution” by elevating the famously capitalist Vice President Nelson Rockefeller to the presidency.

Sara Jane Moore pled guilty to her crime, and served her time, instead of claiming insanity as I thought she should. A member of the Tribal Thumb was convicted of killing Popeye, the other FBI snitch. It has taken me years to connect the dots to understand Moore’s moment in US history, by looking back not only at my own journals and published articles, but also at court records, author Geri Spieler’s biography of Moore, and reporting in Rolling Stone and Playboy.

Sara Jane Moore needed to find another way to break dramatically with the FBI–not just because she was a romantic revolutionary, and desperate to be taken seriously–but because she was trying to save her own life from the radicals she claimed she wanted to join.

She had good reason to believe they would kill her, if they found out she had two-timed them as a snitch. How better to prove now that she was now loyal to their cause, than to publicly break with the FBI in a big story in the newspaper of record in California? When that didn’t work out as she expected, she turned to Plan B: assassinating the President of the United States.

That didn’t work out either. Sara Jane Moore spent more than 30 years of her life in jail. Yes, she was unstable and confused when she pulled the trigger. But wait! She is alive, and is now the stuff of books and movies. Sara Jane Moore became the important person she always wanted to be.